Life of Wifredo Lam

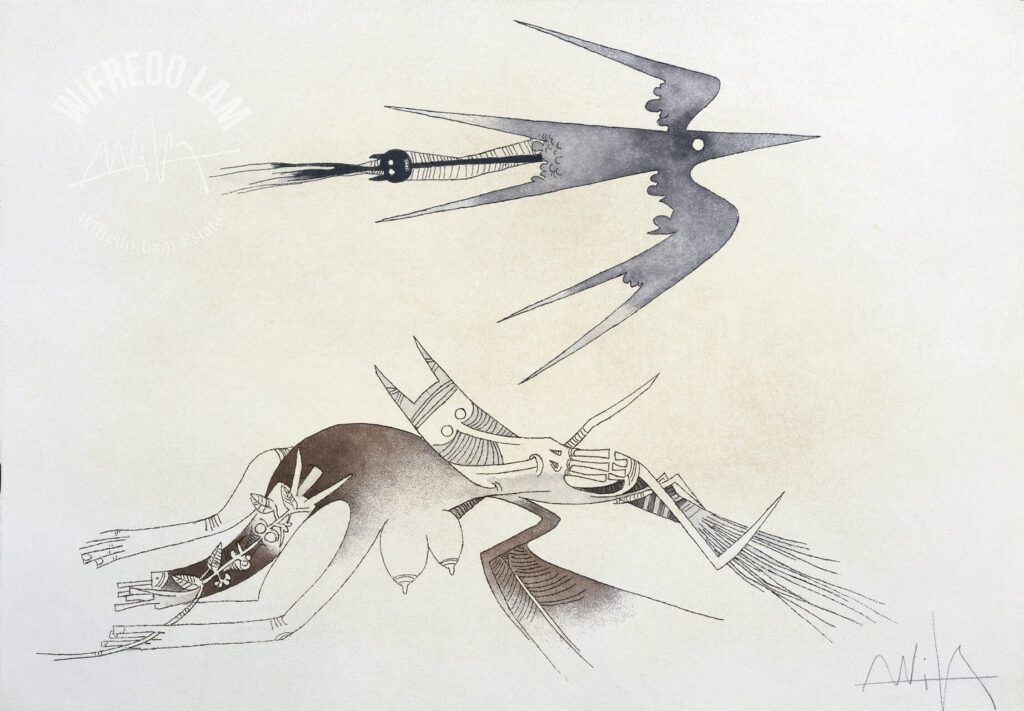

Wifredo Lam is recognized as a pioneering figure of Modernism for his groundbreaking, transnational body of work that challenged and expanded the boundaries of Modern art. Drawing from his multicultural heritage in Cuba and experiences from life across Europe and the Americas, Lam developed a distinctive hybrid visual language creating a singular, complex and highly poetic oeuvre.

His art anticipated and actively participated in the broader project of decolonizing culture, a commitment he articulated when he declared:

“My art is an act of decolonization.”

1902 – 1923

Cuba – Complexity of a mixed heritage and the birth of his art

Childhood in Sagua la Grande (1902-1916)

Family situation (1902)

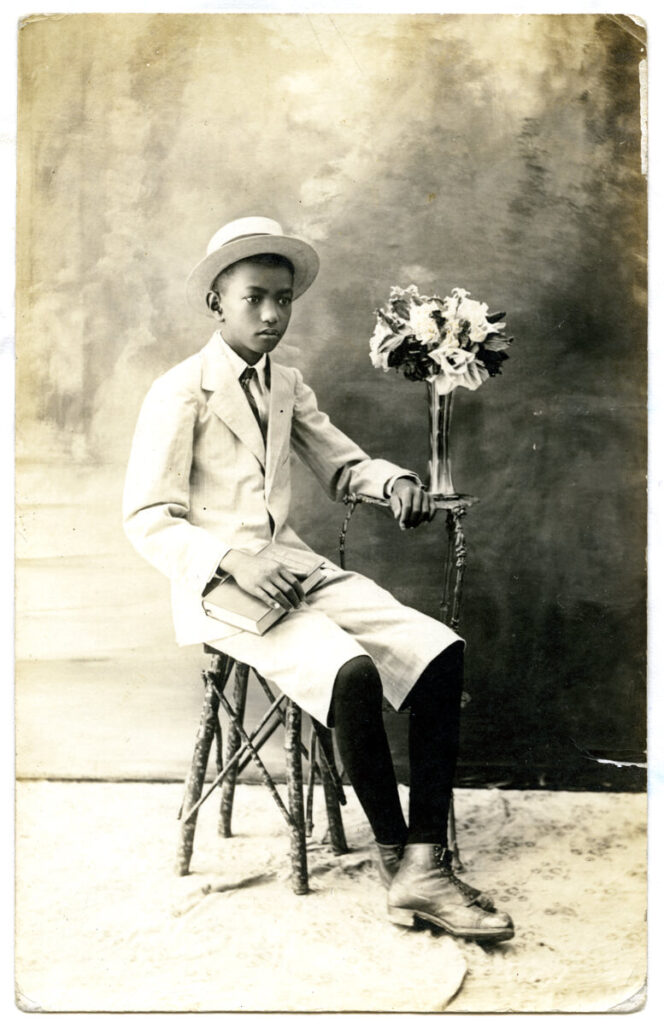

Wifredo Lam was born on December 8th, 1902, in Sagua la Grande – a sugar producing region on the northern coast of Cuba – the year the country proclaimed itself a Republic, after a little more than three centuries of Spanish rule. The youngest of eight children, he was baptized Wilfredo Oscar de la Concepción Lam y Castilla(1). His mother Ana Serafina Castilla was born in 1862 in Sancti Spiritus of mixed Spanish and African heritage. On her African side, she came from a long line of slaves. His father Enrique Lam-Yam was Cantonese, born in China in 1820. He is thought to have left China to work in California and then in Central America before reaching Cuba sometime between 1872 and 1880. He may, however, have immigrated directly to Cuba with his brother Ciu in 1860, fleeing the Taiping Rebellion. In the small town of Sagua, Lam-Yam opened a carpentry business. As he spoke several Chinese dialects, was well educated and versed in calligraphy, he also served the local Chinese community as a public scribe.

Luxuriant nature inhabited by spirits (1903-1908)

Lam grew up in a modest but relatively open-minded family at a time when blacks and mulattoes still suffered discrimination. He spent his childhood in the midst of a “sea of sugar cane” and fertile fields bordered by royal palms, stretching all the way to the horizon. The island has some of the world’s richest faun and as Lam once said, “When I was very little, I was surrounded by my own little jungle.” This atmosphere of luxuriant, brightly colored nature undoubtedly caught his attention very early on. Enrolled in a public school in the neighborhood of Cocosolo, he was above all steeped in a melting-pot of civilizations: the Catholic religion of the island and the faith his mother had adopted; the cult of his Chinese ancestors, practiced by his father in the form of offerings; Cuba’s African traditions, especially black magic as practiced by his godmother, Antonica Wilson. His godmother, “Ma’Antonica” as her godson called her, which is often written “Mantonica,” was a well-respected priestess of Santería. She exposed the young Wilfredo to the rudiments of the religion and its symbolism and often recounted captivating stories as Santería possesses a rich mythical corpus that abounds with the adventures of its anthropomorphic deities.

And while his father – a wise and very secretive man who supported the democratic leader Sun Yatsen and his reformation party – would sometimes recount the dramatic episodes of Asian history, set in the enormous expanses of the Siberian landscape, of Mongolians and Tartars, it was his mother’s stories that had the greatest impact on his imagination. He especially enjoyed hearing about the adventures of José Castilla, a converted and freed man of mixed-race who had his hand cut off by a Spanish crook, and hence his ancestor’s nickname “Mano Cortada” (cut hand). Antonica Wilson, meanwhile, was hopeful her godson would follow in her footsteps and inherit her secrets to become a babalao, a Yoruban word meaning “father of the secret” (divine interpreter of oracles and signs). But the young Wilfredo refused even the initiation stage. All the same, she put him under the protection of the gods, in the care of Chango, the god of thunder, and Yemeya, the goddess of the sea.

A precocious draftsman (1909-1914)

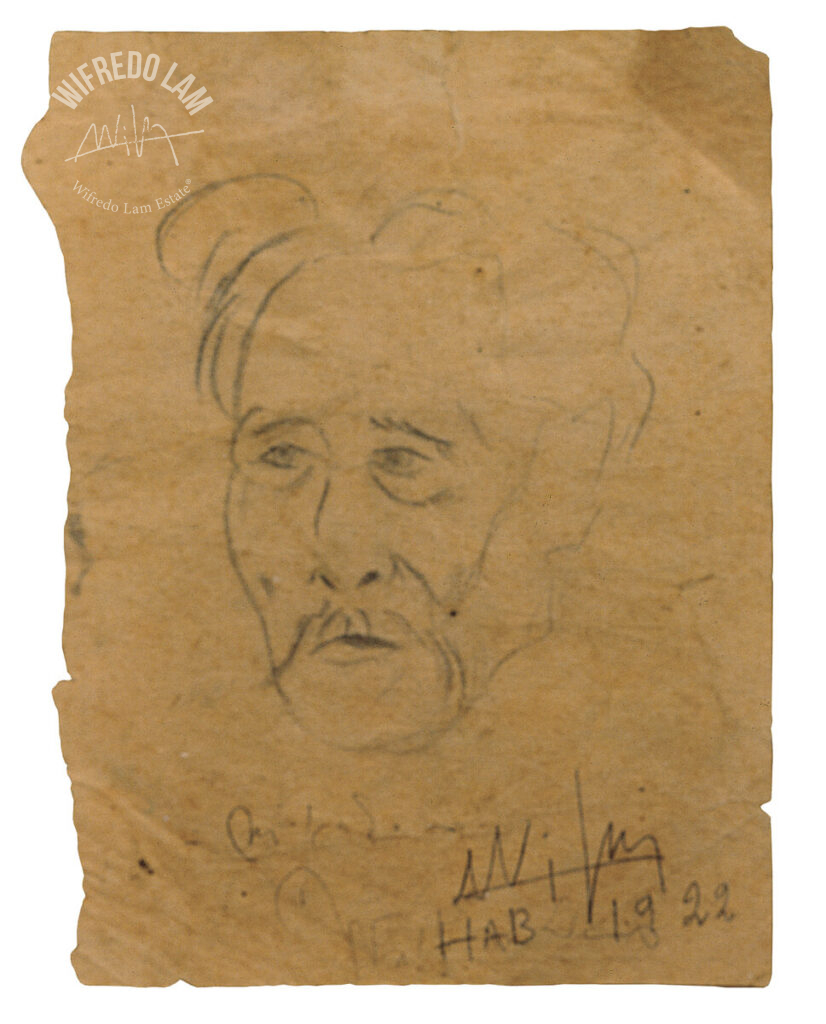

By the age of seven he was already showing signs of an artistic calling, but Sagua lagged behind in cultural development. He may have been shown the mediocre religious paintings that adorn its churches or accompanied his father to the traditional Chinese theater and new-year celebrations. But he did observe the calligraphy of his father and the many avatars of African sculptures in his godmother’s house – artifacts which were forbidden during slavery. He thus simultaneously discovered very different iconographic worlds. He loved to draw (landscapes and portraits) and took a great interest in art books with their black and white illustrations, poring over the masterpieces of Da Vinci, Velázquez and Goya, but also of Gauguin and Delacroix. They were a window to Europe, the prompts that made him vow to one day see the originals at the Louvre and the Prado with his own eyes.

Havana 1916 – 1923

Arrival in the city of light (1916)

Wifredo was sent to Havana in 1916, his first encounter of a large, bustling city. It appeared to him as a city bathed in its own particular light, both dense and airy. The family had hoped the young Wilfredo would go into Law, but he was clearly already on the path to becoming an artist. He visited the city’s Fine Arts museum, created in 1913, discovering its somewhat provincial Spanish and Hispanic Cuban artists and its Greek, Egyptian and Roman artifacts. He went for strolls in its botanical gardens – built a century earlier – and liked to sketch its tropical plants. He was fascinated by the lush leaves and swollen fruits and the striking colors of their flowers. He also scoured the city’s bookshops in search of the latest publications.

Academic training (1918 – 1920)

In 1918 he was enrolled in the Escuela Profesional de Pintura of San Alejandro with the intention of studying sculpture but soon found the stone work too strenuous. He thus became the painting student of the instructors Leopoldo Romanach and Armando G. Menocal. Despite the rather dry nature of the exercises, he preferred painting and drawing still lifes to copying molds and continued to apply himself to his studies with the aim of mastering the art of portraiture. “There was an element of Chardin in what I did as a youth. You see they were never “Spanish” (black, green, purple…) but more refined (or so I tried), for I carry within me a Chinese and a Cuban heritage and this counts enormously. Oh, and I forgot to mention the French influence, which came to me very early on. In other words, very early on a certain nervous tendency in me came through in my writing (which has never gone away) and which is the opposite of the ‘Spanish’ roughness.”

First recognitions (1920 – 1923)

In June, 1920, Lam became a member of the Association of Painters and Sculptors of Havana. Three years later, he exhibited his first paintings at the Fine Arts Salon of Havana, following which he was invited to present his work in his home town of Sagua La Grande. The two events brought him a degree of success, prompting Sagua to award him a grant to pursue his studies in Europe. The director of the Museo Nacional de la Habana, Antonio Rodriquez Morey, provided him with a letter of recommendation, which would give him access to Madrid’s high society.

Anne Egger

(Translation by Unity Woodman)

(1) He lost the “l” to his name following an administrative error in the mid-twenties, from which point the painter adopted the new name, signing his works with the new spelling.

1923 – 1938

Spain - The Spanish Years

The discovery of the old world and his artistic training from master works (1923-1935)

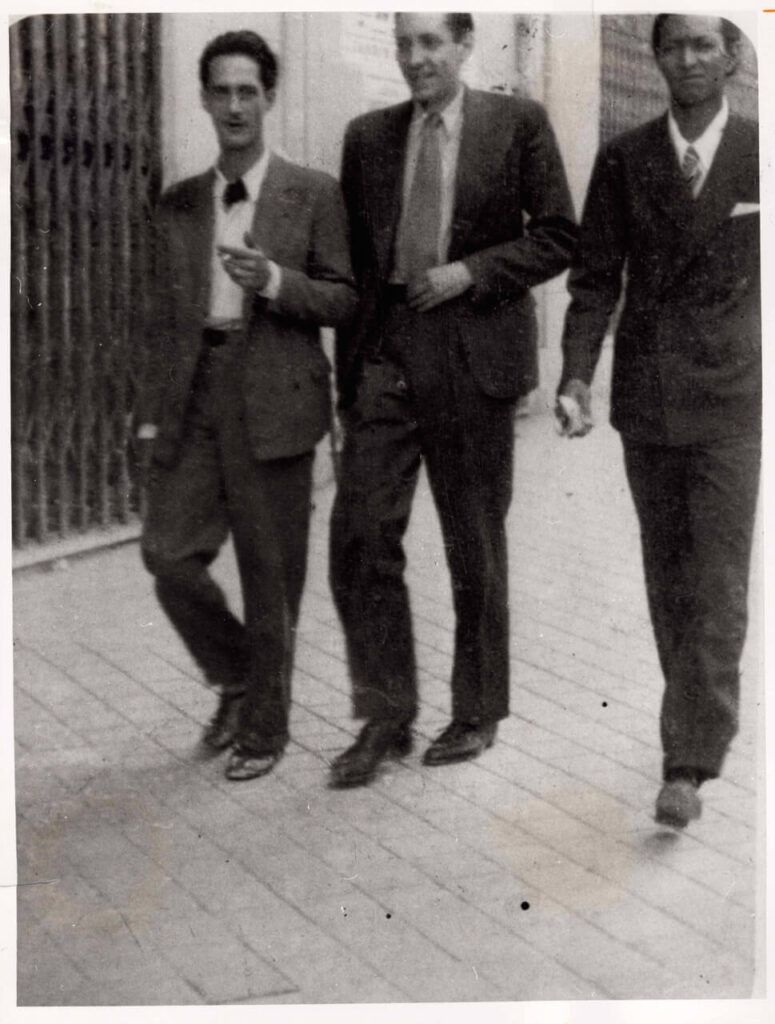

Wifredo arrived in Spain in late 1923, only twenty years after the country lost Cuba, its last colony. In Madrid he made acquaintances with Fernando Rodriquez Muñoz, a well-educated medical student, a touch bohemian, who introduced him to his circle of friends – for the most part art lovers – most notably Baldomero and Faustino Cordõn, a future biologist. Thanks to his letter of recommendation, Wifredo came into contact with the Director of the Prado, Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, an official portraitist of noble birth and a professor at the Real Academia de Bella Artes. He invited Wifredo to study at the academy which introduced the young painter to an artistic climate far removed from the modernity he had hoped to find. He turned to the masters for inspiration on his many visits to the Prado: the mannerist portraits of El Greco and Velázquez, the mythological scenes of Poussin, Goya’s “horrors of war” – what Lam termed “visions of crimes as spectacles of the injustices of a delinquent militarism” – the critique of injustices by Breughel in The Triumph of Death, the hybrid creatures of The Garden of Delights by Bosch, engravings by Dürer – the great witness to the anxiety of his epoch and its superstitions. These artists of revolt with their painted discourses against all forms of tyranny spoke to him directly as he patiently copied them, sending the copies to Sagua to justify his grant. He was also moved by what he saw at the Archeological Museum, which marked his discovery of prehistoric art. Every day, when he left San Fernando, he would make his way to the Alhambra where he was simultaneously enrolled in classes at the Escuela Libre de Paijase founded by Julio Moisés. These workshops were far more experimental approach, thanks to the influence of its non-conformist painters Benjamin Palencia, Francisco Bores, José Moreno Villa and Salvador Dalí.

With General Machado’s rise to power in Cuba, Lam lost his grant and entered a period of dire financial hardship. He began to offer his services as a more or less classical portraitist to the aristocratic milieu of Sotomayor’s circle. During the summer of 1925, his friend Muñoz invited him to visit his family in Cuenca. This small Medieval town, perched on a steep spur in the mountains southeast of Madrid, struck a chord in Lam who set about painting its arid landscape and the poverty of its peasants, perhaps reminders of the disinherited people of his own island. He spent several months in Cuenca, joined by his friend the portraitist Jaume Serra Aleu. They settled in a small studio in the town’s center and mixed with the local artists and intellectuals (Compans, Marco Pérez, Fausta Culebras, Zomeno, Eduardo de la Rica, Vazquez Díaz, Serra Abreu, Rusinol…) who regularly met up at the Iberia Hotel or the Escobar bookshop. For the first time, Lam felt connected to an artistic community, and new influences began to enter his work: the Catalan symbolists (Herman Anglada Camarasa, one of the major interpreters of Andalusian neo-regionalism – and Nestor), followed by the art of Cézanne.

Upon his return to Madrid, he discovered the Vallecas School which was seeking a renewal in its approach to the Spanish landscape. Its founders, Benjamin Palencia and Alberto Sanchez were joined by Canaja and Maruja Mallo and supported by Manuel Angel Ortíz and Guillermo de la Serna. Lam’s paintings of the local landscape and abodes during the summer of 1927 spent in the region of Cuenca are very much in this vein. Shortly afterward, the talk among the avant-garde artists of Madrid openly addressed Surrealism—a movement created in Paris four years earlier. The painter Benjamin Palencia, recently returned from Paris where he had met Picasso, Braque and Matisse, was the first to show works of Surrealist inspiration. Other painters were soon to follow: José de Togores and José Moreno Villa. Always curious about the latest tendencies in art, Lam made attempts at automatic writing. This was also when he made his discovery of the masks and sculptures of Guinea and the Congo as they were on exhibit at Madrid’s archeological museum. In 1929, a large exhibition of Spanish painters living in Paris was held at Madrid’s botanical gardens with the sculptors Apeles Fenosa and Pablo Gargello, the painters Juan Gris, Manuel Angel Ortiz, Pablo Picasso and Pedro Pruna. What struck the young painter above all was the formal energy that emerged from the works of Picasso. According to Lam, the revelation was both of a pictorial and political nature. It made him want his own paintings to convey “a general democratic proposition […] for all people.” This declaration undoubtedly reflects how the painter felt about the alarming social situation in Cuba under Machado’s dictatorship, a situation he was able to follow closely from the letters he received. In the company of his friends Muñoz and Cordón who exposed him to the ideas of Marxism, Lam awakened to a new political awareness. Likewise, he began frequenting the Sunday gatherings of a group of Latin American belonging to the Hispanic American University Federation. Wifredo Lam and Eva Piriz, whom he had met two years earlier, were married.

Political and domestic economic crisis (1930 – 1933)

The economic crisis in Spain had dire consequences for Lam’s own financial situation. Despite the penury of the newly weds, however, the birth of their son, Wilfredo Victor, brought them much joy. The painter flourished in his new family life, taking a sharp interest all the while in the world of art. The Autumn Salon presented the symbolist and surrealist works of Angeles Santos that may well have inspired his own. But his happiness was short lived: Eva and the child both died of tuberculosis in 1931. This double loss plunged Lam into despair. In his letters, he speaks of being “disgusted,” “revolted” and “neglectful.” And while a trip to Cuba to see his family again was much on his mind, the conditions were far from favorable: the repressive politics of Machado reigned over the island even as Spain was on her way to becoming a Republic, following the overthrow of the monarchy. Only the support of his friends Faustino Cordón and Anselmo Carretero, the latter an engineer in training, kept him from going under. They found him commissions for portraits to ensure he had enough money to eat. But he worked little, choosing instead to spend his time reading, in particular historical and ethnographic books on Africa and slavery. During the summer of 1931, he and his friend Anselmo Carretero made a trip to León, a mountainous region in the northwest of Spain where they befriended a small group of local artists. Gradually, Lam regained his spirits. The great discoveries of this period included the latent cubism of Cézanne, the exotic primitivism of Gauguin and the impressionist naturalism of Franz Marc.

In Madrid, Lam and Faustino Cordón frequented the café on the Gran Via, a meeting place for a wide range of intellectuals: Juli Ramis (a painter he shared a studio with), the writers Azorin (José Martinez Ruiz) and Ramon del Valle-Inclan, the poets Federico García Lorca and Jorge Guillén, the Cuban painter Maria Carreño, the Guatemalan journalist and poet Miguel Ángel Asturias, an amateur of pre-Colombian culture. Their debates focused on the emerging Republic and their growing concerns about the rise of the conservative opposition and of fascism in general. These fruitful meetings reawakened Lam’s enthusiasm, but did nothing to assuage his fears about Cuba, as letters from his family and friends brought him news of a new wave of terror sweeping the island – assassinations, torture, prison, labor camps but also of the organized resistance and press campaigns against Machado’s dictatorship. Cuban exiles in his entourage corroborated these reports. In 1933, on the brink of disaster, staying informed about world events was imperative – one could no longer be a bystander. Hitler was nominated Chancellor of the Reich and new anti-Semitic laws were enforced; the Cuban people succeeded in bringing down Machado and forced the “Tropical Mussolini” to flee to the Bahamas but within a month Batista’s military coup d’état had already set in place another dictatorship; in Spain, the elections put the rightwing back in power for a three-year term – an increasingly extremist right wing.

Politically, Lam stood firmly to the left, decisively Marxist in sentiment but free of dogmatism. He participated in the first exhibition of revolutionary and anti-fascist art at the Athenee and made contact with different activist groups fighting imperial dictatorships: the Asociacion general es estudiantes latinoamericanos (AGELA), the Organisacion anti-fascistes, the Federation universitaria española and the Comiyé des Jovenes Revolucionares Cubanos to which his compatriot in exile and new friend, the self-taught painter Carlos Enríquez Gómez, belonged. He was also introduced to the Cuban Alejo Carpentier, who had been living in Paris for five years. Carpentier, a musicologist and writer had his novel Ecue-Yamba-O published that same year Ecue-Yamba-O – among the first Afro-Cuban novels. At the Prado, Wifredo met Balbina Barrera, an amateur painter who, like himself, enjoyed copying the master painters. She and Wifredo would remain very close for several years.

Crisis of inspiration 1934 – 1935

Lam entered a period of self-doubt – at once an existential and artistic crisis – that prevented him from painting. He continued to read a great deal: classics of the Spanish language; contemporary poetry, including an anthology of Iberian poetry prefaced by Lorca who attempts to explain the secret of the Góngora language, the Persian poet Omar Khayyâm and the pre-Romantic William Blake; Thomas Mann; Russian novels from the 18th-century up to Nikolai Gogol. He also read various works on historical materialism, exploring the revolutionary writings by Russian and German theorists his friends Fernando Muñoz and Faustino Cordón recommended to him. And furthermore, he studied books on art covering the work of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse and the German Expressionists, particularly Franz Mark.

In his modest one-room flat in Madrid, Lam struggled with his doubts. For a year, he painted the view from his window, trying out different chromatic formulations, which are primarily influenced by Matisse. He spent the summer of 1935 in Malaga – a small Andalusian seaside resort and the birthplace of Picasso – with Balbina and her six children. The city’s Museo de Bellas Artes, founded in 1923, presented Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque collections with works by Ribera and Pedro Mena. On his way back to the capital, he passed by Grenada to visit the Alahambra, undoubtedly invited by Lorca. Back in Madrid, where his friends welcomed him, he discovered the first issue of Caballo verde para la poesía, founded by Pablo Neruda and Manuel Altolaguirre.

The combat for liberty (1936 – 1938)

In February 1936, with the victory of the Frente popular and its wave of social reforms, there was much celebration but Lam was still faced with his creative block. In light of the anti-Republican military insurrection on July 18, he saw painting as secondary. The Spanish Civil War had begun. In three days, a third of the country was overcome by Franco’s partisans, but Madrid and Barcelona put up strong resistance. Lam learned of the assassination of Lorca in Grenada and Neruda’s recall from Madrid, while others arrived to support the Republicans: Carl Einstein who joined the Durutti Column or the Cuban war correspondent Pablo de La Torriente Brau, who died in combat in December. Lam and his friends signed up to the war effort. Following the example of Mario Carreño, Lam began designing posters for the ministry of propaganda to extol the glory of the Republicans and then participated in the defense of the city that had come under siege in November. Above all, there was a need for ammunition. His chemist friend, Faustino Cordón, found a position for him in an arms factory and he was given the job of assembling anti-tank bombs.

After six months of intensive work handling explosives, Lam suffered from poisoning due to his contact with the chemical products. In March 1937, he was sent to convalesce in the sanatorium of Caldes de Montbui, north of Barcelona. On his way through Catalonia, he stopped briefly in Valencia where he met Perez Rubio and Joseph Renan. As the Director of Fine Arts for the Spanish pavilion for the International Exhibition in Paris, Renan commissioned a painting from Lam on the theme of the war, but by the time Lam completed La Guerra civil it was too late for it to be exhibited. He continued on through Barcelona in the month of May when the anarchists of the Poum were being sacrificed by the representatives of the Communist Party.

The freedom to paint (1938)

Once settled in Caldes, he was constrained to spend a month recovering. To pass the time, he took up reading again (The Life of Leonardo Da Vinci by Freud; Rembrandt by E. Ludwig; studies on Matisse and Picasso; Othello by Shakespeare; works by Bakunin on historical materialism…). Meeting the sculptor Manuel Martínez Hugué, or Manolo as he was called, and hearing his accounts of his encounters with Picasso, his friend since 1904, his travels with Braque and Maurice Raynal in Normandy opened up new horizons for Lam. Manolo was also one of the first intellectuals to have recognized “Negro art” and one of its first collectors. The sculptor would talk for hours about African statuary, about the simplification of its forms, its rhythmic reach for the essential, for an expression of essence, of the irrational… It was these discussions that seemed to triumph over all forms of totalitarianism and Manolo who incited Lam to make his way to Paris to meet Picasso.

From September 1937, he settled in Barcelona where he came into contact with a much more dynamic artistic community than in the capital. He joined the painting and sculpture section of the Ateneo socialista, which gave him access to a library and a café, and to live models to paint his nudes. Manolo introduced him to the painter Jaume Mercadé and to the photographer Fritz Falkner, who became his new friends. This is where Lam finally set to work and made his definitive break with academicism. Indeed: “The revolution changed my writing and my way of painting,” he once said. With this new sense of encouragement, he set about painting intensively. “I think I must have painted some two or three hundred canvases that I never saw again because, when I left, I gave them to a friend who is now dead.” In the beginning of the year 1938, Lam met Helena Holzer, a young German doctor in chemistry and the director of the tuberculosis laboratory at the Santa-Colomba hospital where she worked for four years. Franz Falkner introduced them to each other in a café on the Lesseps Plaza. The day after Franco’s offensive of April 15, which marks the triumph of Fascism and Catholicism, Lam chose to leave Spain behind him….

Anne Egger

(Translation by Unity Woddman)

1938 – 1941

Capital encounters – France

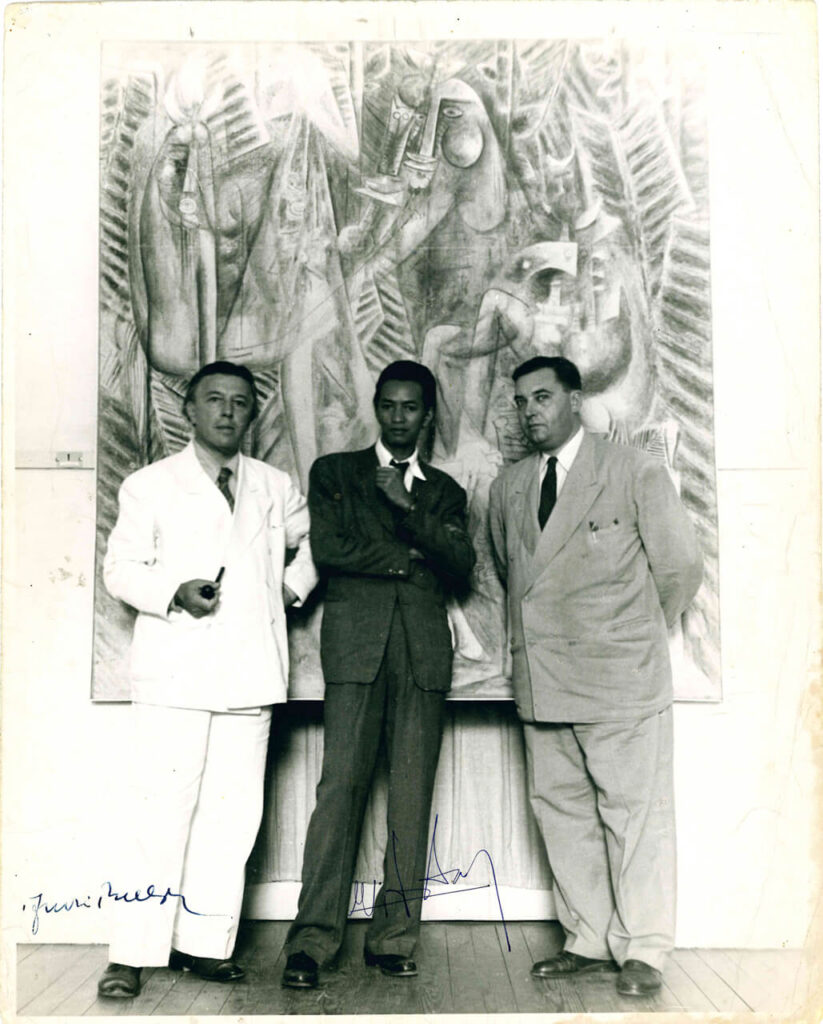

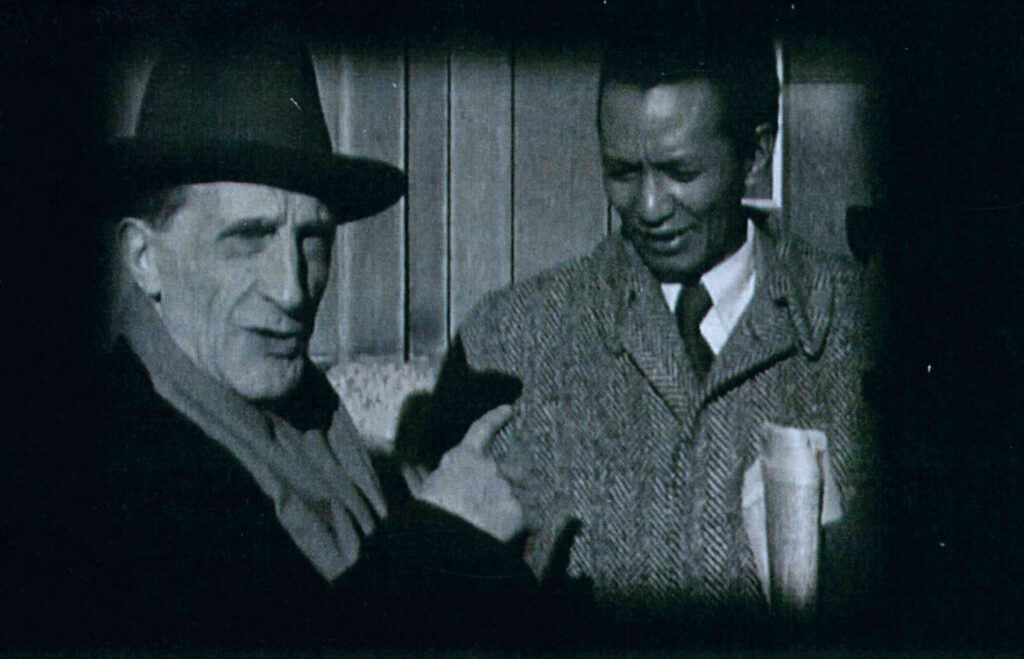

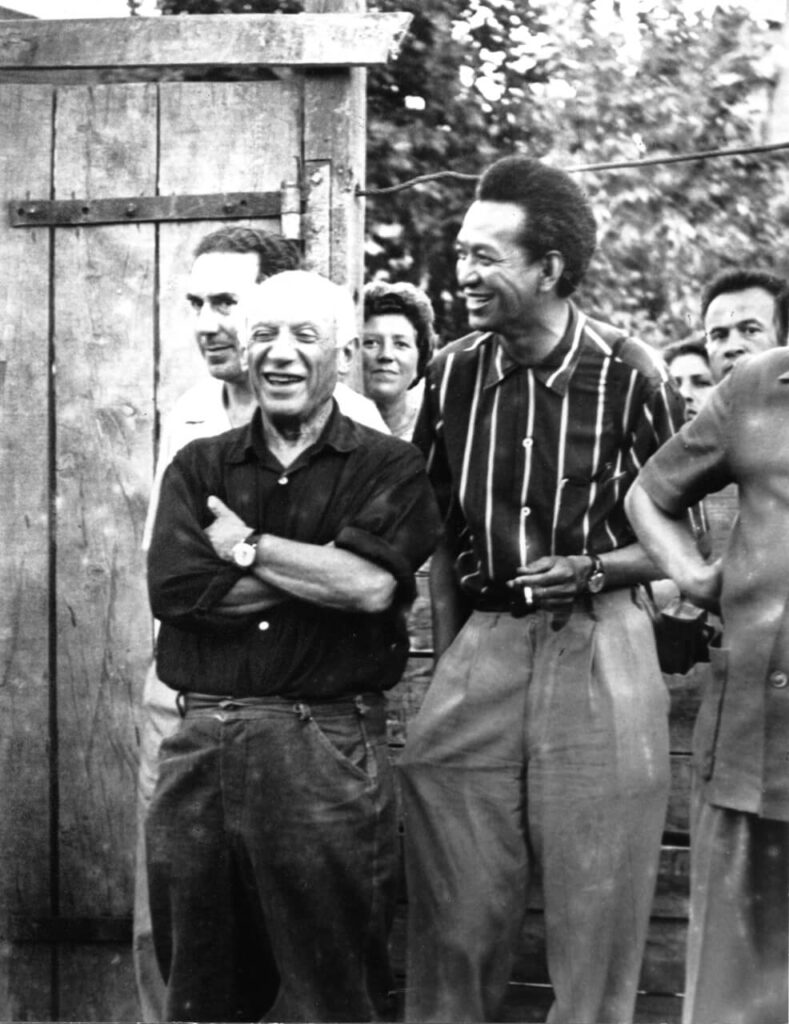

When he arrived at Paris’s central station, Gare d’Orsay, he found lodgings in an attic room in the Hôtel de Suède on the Quai Saint-Michel, not far from the police headquarters, which would soon become, his being a foreigner, an all too familiar place. He explored Paris on foot, meeting up with his old friends Mario Carreño, Alejo Carpentier and Pablo Neruda who, along with César Vallero, had founded the “Groupe hispano-américain d’aide à l’Espagne” (The Hispanic American Group to Help Spain). He visited the Louvre which was currently exhibiting English painting with works by Reynolds, and then the Galerie des Beaux-arts which was exhibiting the Impressionists Renoir, Cézanne, Van Gogh and others. Lam was both intimidated and fascinated by the idea of meeting Picasso. But even before the set visit to his studio on Rue des Grands-Augustins, as Lam clutched his letter of introduction from Manolo, Picasso welcomed him with open arms; indeed, for both of them, it was “love at first sight.” An unwavering friendship was born, a deep bond between these two artists who had traveled opposite but converging paths, joined in their struggle for creative freedom. “My meeting with Picasso and with Paris was like an electric shock…” For Lam, Picasso represented the epitome of boldness and his entry into his artistic life was like meeting an “instigator of freedom.”

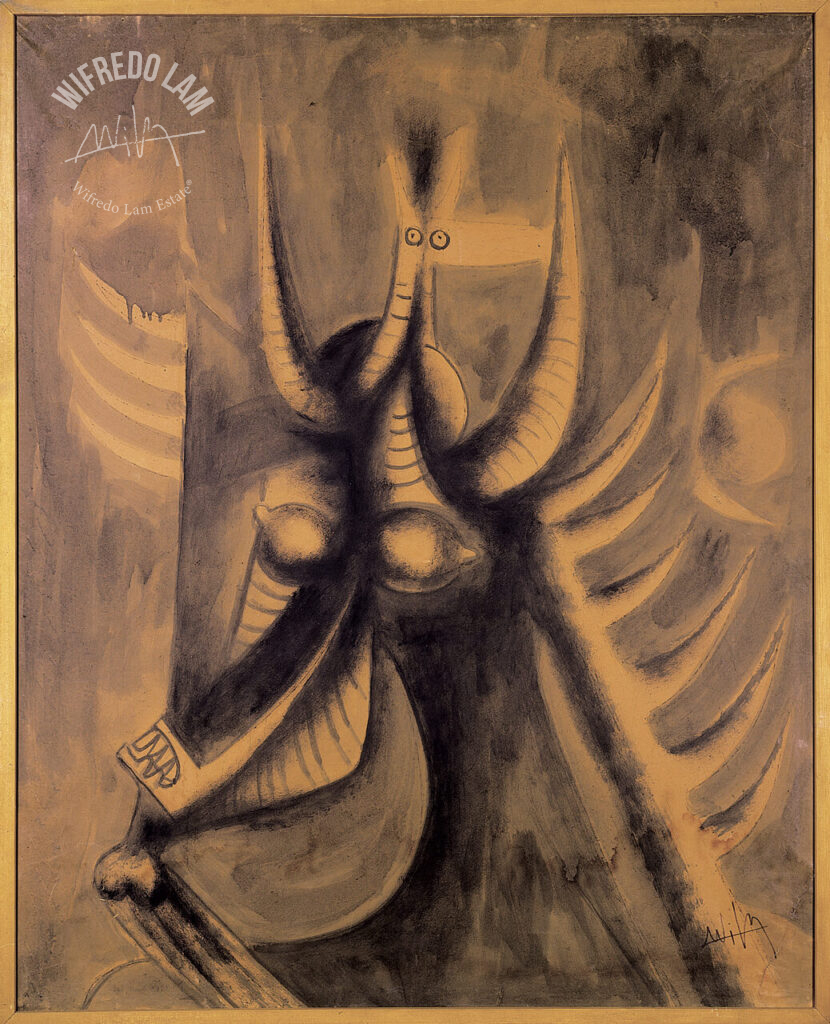

When Lam visited Picasso’s studio, he was captivated by his African art collection, especially a helmet mask of the Baule tribe (Ivory Coast), a round head with antelope horns and a crocodile’s jaws. What drew him to Picasso’s art was the “presence of the aesthetic and spirit of African art.” “Negro art” was a revelation to Lam who was immediately sensitive to its power and energy and its striking independence from the real. Faced with Picasso’s art and what had become a general fascination for the archetypal figures of ancient civilizations, Lam brimmed with questions, prompting Picasso to introduce him to the young poet and ethnologist Leiris, the person he felt was most suited to guiding the Cuban painter in his quest for understanding “Negro art.” Leiris was a former surrealist, whose circle of friends included Pierre Mabille and the sulfurous Georges Bataille, the brother-in-law of the art dealer Daneil-Henry Kahnweiler. That very evening, Lam dined with Leiris, Picasso and Dora Maar, in what was the first of almost daily gatherings, until Picasso returned to the south of France. Picasso introduced his Cuban “cousin” to Henri Matisse, Fernand Léger, Georges Braque, Nusch and Paul Eluard, Tristan Tzara and the Catalan art critic Sebastien Gasch.

Michel Leiris was employed by the Musée de l’Homme, the city’s ethnological museum, in its Black Africa department. With his wealth of knowledge about the magic of the “savage arts,” Leiris guided Lam through the museum’s new halls and its reserve collections of African statues, Oceanic masks, Australian totems…. Here at last, Lam was face to face with art untainted by the tyranny of a bourgeois intellectualism. Through Leiris, he met the scholars Georges-Henri Rivière, who was also passionate about music – himself a jazz pianist – and Léon Gontran Damas, who, along with Césaire and Senghor, was one of the fathers of Negritude. Senghor was passing through Paris after a mission in Guyana. Leiris steered Lam to the city’s specialized galleries, to major exhibitions, and to Pierre Loeb’s and Charles Ratton’s collections. During the summer, Leiris introduced him to André Masson who had just returned from several years in Spain. He also met Joan Miró and other artists affiliated with Surrealism, among them Oscar Domínguez and Victor Brauner. Instead of letting himself despair about the international situation – news from Cuba, the Munich accords – he plunged into his work: “I painted both night and day, although I wasn’t ready to show my work. Paintings piled up in my small hotel room and I could no longer, so to speak, move or paint.” In the autumn, he was presented to André Breton and Jacqueline Lamba; they had just returned from Mexico. His first visit to the studio on the Rue Fontaine was a magical experience. Lam was captivated by Surrealism and the opportunity it offered to access the unconscious through automatic writing: “Surrealism allows for deliverance from cultural alienation,” he once said, and for unearthing one’s true self.

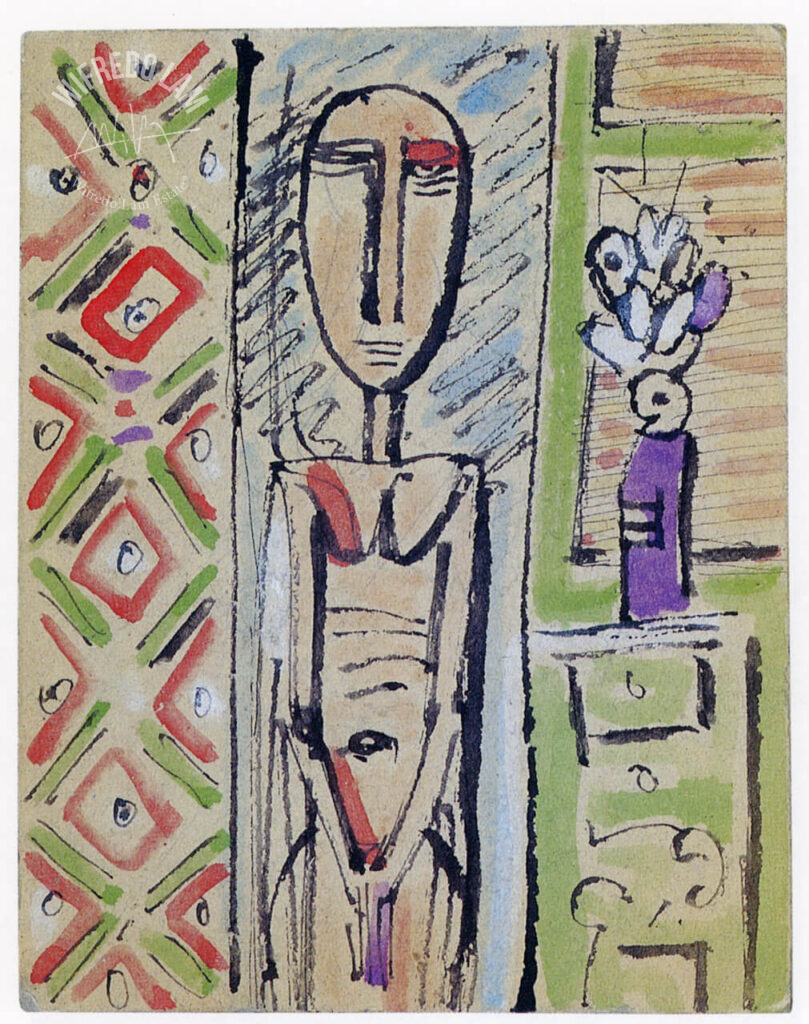

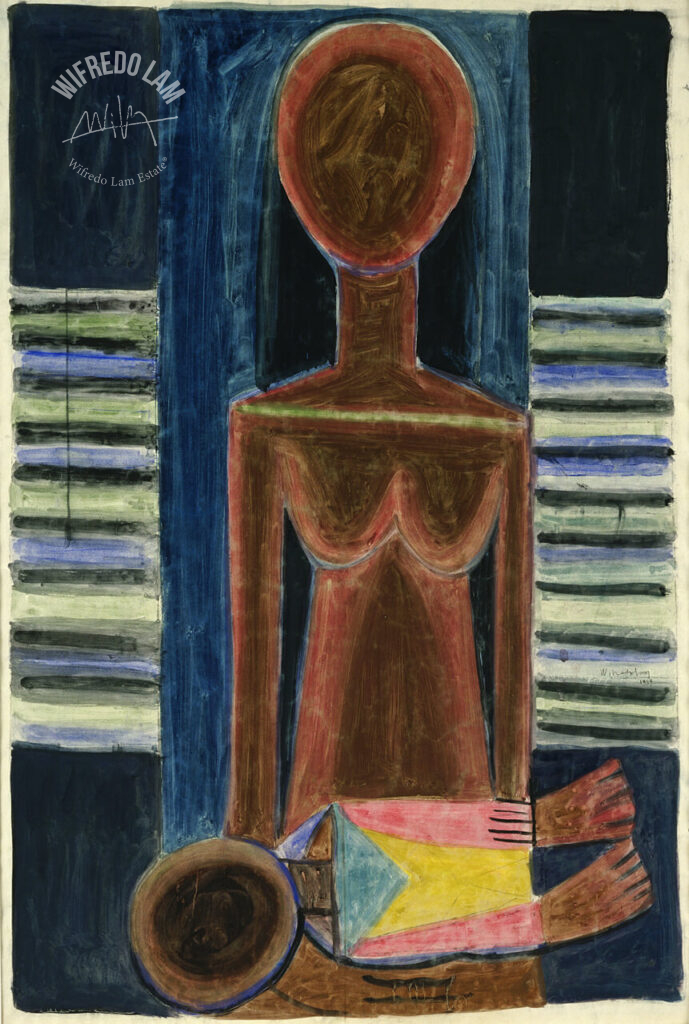

The doors of Surrealism had opened to him. In a café, he met up with Benjamin Péret, who had fought in Spain in the Poum division, and his companion Remedios Varo, as well as Yves Tanguy and Hans Bellmer, who had escaped Nazi Germany. He met Roberto Matta, Wolfgang Paalen and Esteban Franès Kurt Seligmann – all present at the exhibition of pre-Colombian art organized by André Breton at Charles Ratton’s gallery entitled Mexique. Lam was welcomed into a circle of artists and intellectuals who had spent their lives militating against racism, against any form of discrimination, against all abuses of the colonial system…. It was a milieu that had already taken stock of the notion of oppressed identity and whose international resistance applied to all forms of fascism. His work became more “personal” in scope during his Parisian period. He painted frontal, hieratic figures, at once minimal and monumental. These paintings are totemic representations of loss and tragic portrayals of maternity. In their formal simplicity, already begun in Spain, they show undeniable affinities to the work of Picasso. “Our plastic interpretations intersected,” Lam would explain later, and even went on to claim there had been a “saturation of spirit.” He felt a sense of freedom. Masks emerged in his paintings and the act itself of painting proved to be a means of expression for describing the condition of his soul, its pain of loss. The paintings of this period all show isolated, schematic and often speechless figures – emaciated, austere and suffering. He expressed himself as an atheist, fascinated by the magic arts, the magic of animism.

News reached him of the fall of Barcelona on January 26, 1939, dashing all hopes of a Spanish republic. Among the 500,000 refugees who fled into France, he happened to meet Helena Holzer who had just reached Paris. Breton introduced him to the erudite scholar Pierre Mabille, both an ethnologist and a surgeon. During a rendezvous at the restaurant Les Deux-Magots, Mabille sensed that hiding behind Lam’s reserve was a philosophical and cultural astuteness. He was enthralled by the elegance of the Cuban artist’s drawings and talked of their “staggering freedom.” Similarly to Christian Zervos, the publisher of Cahiers d’art, the gallery owner Pierre Loeb, who was by then a close friend of Lam’s, offered to sign a contract with him for the second time and decided to exhibit his work. Newly immersed in this supportive artistic brotherhood, Lam found the stimulation and confidence he needed to at last show his work, which he had hesitated even to show to Picasso: “I’ll never forget that moment. I keep it engraved in my heart and in my memory and go back to it again and again, like the great paintings and books that made me the man I am.” Picasso “showed his approval by freely linking his arm around my shoulder where I felt his hand flutter on my back. At which point I heard him say, ‘I was never wrong about you. You are a painter.” Picasso found him a studio in the 15th arrondissement on Rue Armand-Moisart, near Montparnasse. He worked there often and with greater spontaneity, a place where he received such friends as Carl Einstein, Pierre Loeb, Picasso, Dora Maar, Jacqueline Lamba and André Breton. The exhibition at the Galerie Pierre took place from June to July, 1939, and was viewed by the Paris art scene as a revelation.

Exodus and Collective Works (1940 – 1941)

Lam continued to paint all the way up to the lightning offensive of the Germans in May, 1940. Being of German nationality, Helena was arrested and consigned to the Gurs Camp (in the Pyrenees). When the enemy army headed toward the capital in early June, Lam, who was deeply distraught by having to leave, nevertheless followed the exodus of Parisians and began the long trek on foot to Bordeaux. The Armistice, signed by General Pétain on June 22, incited him to continue on to Marseille where over a hundred intellectuals hostile to the Nazi regime were trying to leave the country, among them many of his surrealist friends. Helena, once freed, joined him there. These various personalities were given assistance from the Emergency Rescue Committee headed by Varian Fry and Daniel Benedite, which allotted Lam a small pension.

Although Lam was preoccupied by the general situation and anxious about having to make his morning rounds to the prefecture, his stay in Marseille proved stimulating: “I made many strong ties with the surrealists during the Occupation.” Together they formed a “very large family, with Breton and Benjamin Péret, Victor Brauner and Domínguez, who was Spanish and my great friend.” Among his other friends were Max Ernst, Hérold and Mabille. “I was impressed by the poetic aspect…a great combat for creation…we worked as a group for almost a year. It was the period of cadavres exquis and many inventions.” The friends came together at the Villa Air Bel or at the Brûleur de loups café on the old bridge. They created collectively to pass the time and to alleviate their anxiety: drawings, collages, cadavres exquis, automatic writing, games of truth and a new Marseille tarot. They discussed and shared their readings.

During the winter of 1940 – 1941, Lam and Breton developed mutual respect for each other. The poet had the gift of recognizing budding talent and sensed Lam would create a visionary world in the future. When Breton asked him to illustrate his poem Fata Morgana, a poem full of his Mexican impressions, Lam set to work and produced hundreds of ink and pencil drawings, which are particularly prescient of his future signature style. In March, six of his drawings accompanied the printing of five copies (published by Editions Sagittaire), but the book was blocked by the censorship commission, forbidden on the grounds that Breton was suspected of being an anarchist and that his work was a “negation of the spirit of national revolution.” Its illustrator, they claimed, represented the incarnation of both degenerate art and racial impurity. But departure was imminent and a last exhibition-sale was organized of their paintings in the garden of the Villa Air Bel. Peggy Guggenheim bought two of Lam’s gouaches. He thus left the country with a few bank notes and, above all, the encouragement of both Picasso and Breton – a fine gift for braving his exile.The “Ship of Fools” sets sail for the Caribbean (1941)

On March 25, 1941, the little steamer Capitain Paul-Lemerle headed west, on board ship Wifredo and Helena, André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba and their daughter Aube, Victor Serge, once a close companion of Lenin’s, his family, Anna Seghers and 350 other intellectuals threatened by the Vichy regime and the German police. “When the time came to embark the quayside was cordoned off. Helmeted gardes-mobiles, with automatic pistols at the ready” – or so reads an episode described in Tristes Tropiques by one of their companions, Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Poetic call at Martinique

Marseille, first raw from left to right : J. Hérold, H. Lam, W. Lam, A. Gómez. Second raw : Pino, H. Gómez, friend of Pino, J. Breton, A. Breton. Third raw : O. Domínguez and his friend

On April 24, the passengers met with an icy reception in Martinique. Viewed by the Vichy regime as “deserters,” they were immediately interned at the Lazaret camp, where they spent over a month – the fate of all foreigners and French people suspected of leftist leanings. Jacqueline, André and Aube Breton, however, were allowed to settle in Fort-de-France, where they were soon met by André Masson and his family, who arrived on a later boat. On some days, Lam and Helena were given leave to join their friends in the capital. Breton discovered the review Tropiques and met its founders Suzanne and Aimé Césaire and René Menil – a key encounter for all involved. Breton and Lam embraced Martinique’s great poet as the messenger of a new era; as for Césaire and Lam, they were indebted to Breton for his “brazenness,” for pointing them to such uninhibited choices, and for saving them precious time. Surrealism had opened the way for them to invent forms of expression and representations deeply anchored in their heritage: an approach steeped in the vernacular of Antillean culture and the animism inherited from Africa. Surrealism was a Western technique for becoming African. For Lam, these encounters put his hesitations to rest once and for all. Césaire organized excursions of the island, and Lam took in its exuberant vegetation, bursting with life, with a sort of fascination: “It was his first true meeting with tropical nature,” Césaire would recount. He was fascinated by the “savage beauty of the island, the generous slopes of its mountains, rich with such varied, dense vegetation, overflowing with life, with sap, making each plant swell, fantastical intertwining and tangled trees,” wrote Loeb. There “he was revealed to himself. The tropical way of looking at things had replaced the Spanish. He now saw this landscape and it created a deep shock. His painting changed.” While Lam discovered Césaire’s exalted world of imagination, Césaire, for his part, declared, “Lam is a poet” and “a man of the Antilles” about to plunge more deeply into his Afro-Cuban identity. Césaire called him “the great artist of Neo-African painting.” Suzanne and Aimé organized a reading that again had significant impact on the Cuban painter… The Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land), which Césaire wrote in 1938, was a song praising the dignity of the Negro, a great affirmation of his being and genius, uniting “the barest, most direct outcry from the bowels of man of the misery of the Black man in the very heart of this floral magnificence.” Lam found an echo in this fight against injustice and colonial despotism championed by Césaire, Senghor and Damas… He had essentially found a brotherhood. The review Tropiques also embraced and inaugurated “the passage of Wifredo Lam, the astonishing Negro Cuban painter in whose work we find, alongside the best teachings of Picasso, a curious and wide intermingling of Asian and African traditions” (issue n°2, 1941).

A stop-over at Saint-Domingo

On May 16, 1941, the exiles once again embarked on a ship, a cargo ship this time, the Presidente Trujillo, which took them to Guadeloupe where Mabille had been living for a year, although he was already preparing to leave for Haiti, weary of living under the Vichy regime. Their voyage continued on to Saint Thomas and Saint-Domingo, a port of call to obtain their visas. Lam met Eugenio Granell who was living in exile there. He interviewed these erudite figures – Breton, Victor Serge and Mabille – for the newspaper La Nacíon. During their daily meetings, others soon joined them: the abstract Spanish painter José Gausach, the Austrian portraitist, George Hausdorf, the sculptor Manolo Pascual who taught at the National Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1939, and the Dominican artists Yoryi Morel (a master of local folklore), Jaime Colson (who had met Braque and Picasso in Paris) and Dario Suro (a student of Diego Rivera’s). The friends had to part ways as only the Breton and Masson families were given permission to continue on to New York, while Lam and Serge, who did not receive visas for Mexico, had no choice but to sail on to Cuba. In August, after five months of this journeying and an absence of seventeen years, Lam reached the shores of his native island.

Anne Egger

(Translation by Unity Woodman)

1941 – 1945

Cuba, forced exile to the native land

Return to flamboyant nature (1941 – 1943)

Upon their arrival, Lam reunited with his family – his mother, Serafina, and his sisters Eloísa, Teresa and Augustina. The prodigal son had returned. Despite this moving reunion, Lam felt an uneasy sense of no longer belonging, of being uprooted. He hardly recognized his own country. Havana had changed “with its white capitol, the mark of America, its banks, its palaces, its luxurious European shops.” The city flourished but it was all mercantilism and the cultural climate was deplorable, dominated by art that was either overly academic or folkloric. He began to reconnect with a past he thought had disappeared and managed to reconstitute a fluctuating core of friends, acquaintances from the past and other exiles from Europe who arrived before him: Carlos Enríquez, Mario Carreño, currently a teacher at the San Alejandro, Nicolas Guillén, Manuel Altolaguirre and Alejo Carpentier, whom Lam would see frequently; and on their way to Mexico, Remedios Varo and Benjamin Péret who spent the autumn in Cuba. Lam maintained an epistolary relationship with his other friends, as promised. Breton spoke highly of Lam’s painting to the New York gallery owner Pierre Matisse who took him on contract and proposed to exhibit his work the following year. A return to work was imperative, but how would he go about it? “I thought back to Europe being invaded by the Nazi army with great sadness… For me, seeing Europe had been everything. When I came back to Cuba, I was taken aback by its nature, by the traditions of the Blacks, and by the transculturation of its African and Catholic religions. And so I began to orientate my paintings toward the African.”(2)

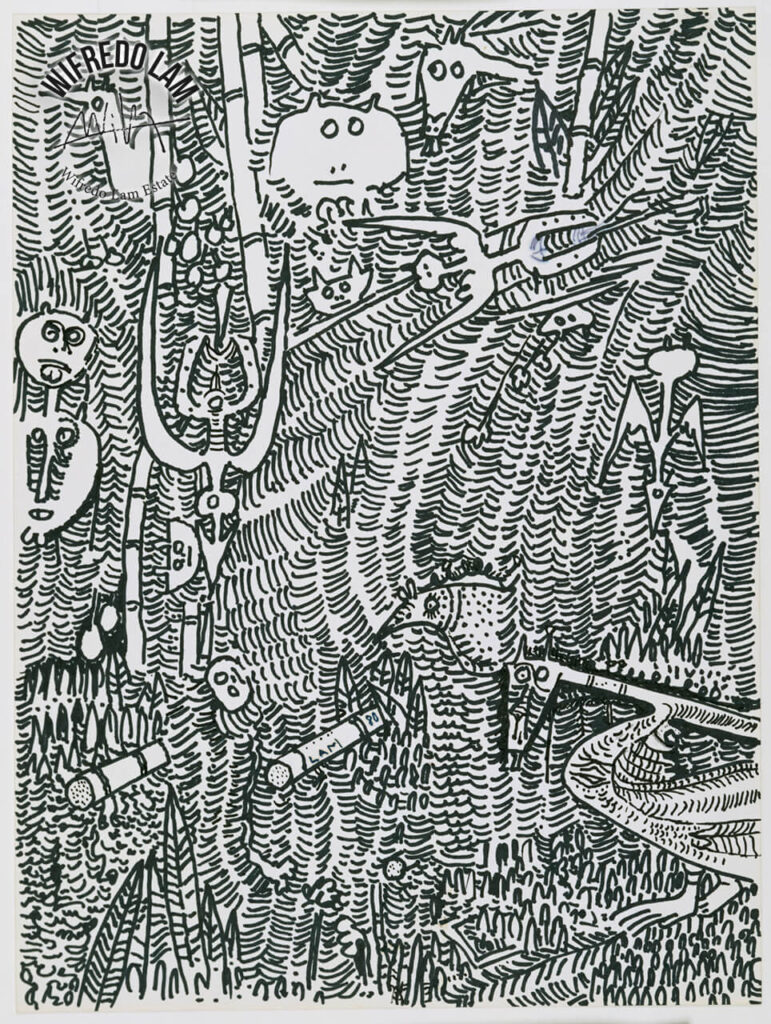

To begin with, he reconnected with his natural surroundings – the rows of flamboyant trees, fields of sugar cane – and then with his compatriots. He reflected on the striking contrast between the frivolity of Havana’s tourism and the miserable condition of the blacks in the countryside, for whom discrimination appeared to have worsened with Batista: “What I saw upon my return looked like Hell.” “All the drama of the colonialism of my youth resurfaced in me”. Lam turned to painting, not as an escape but as a way of denouncing, of contesting what he was witnessing. Like a lone soldier he set about painting the drama of his country, the cause and the spirit of the Blacks, their aspirations for liberty. And, to stand out from all folklore and its pictorial manifestations as advocated by Cuba’s political parties, he began to invent his own language. In his canvases, surreal, phantom-like, spectral, vengeful, denunciatory, almost hallucinatory figures rose up, playing out their drama within exuberant vegetation where faun and flora blend and multiply. His visions thus re-actualized what had been subjugated and shrouded in the depths – images he hoped would be “capable of disturbing the dreams of the exploiters”. For, in his mind, a true painting “sets the imagination to work.” And hence, thanks to his project, Africa could re-enact its entry into the Caribbean. In February, 1942, Lam and Helena moved into a large house surrounded by the luxuriant vegetation of its garden, giving him an ideal space to paint. He set about painting with great fervor, in lieu of the exhibition being planned in New York. Pierre Loeb and his family, who also spent the war years exiled on the island, were happy to reconnect with them. In discovering Lam’s most recent paintings, Loeb saw this forced exile in a positive light. “It was his chance. He renewed his contact with the tropics, which he breathed and penetrated, becoming one with it.”

Santería and orishas (1942 – 1943)

It was also a return to the old beliefs of his childhood. He was introduced to Lydia Cabrera, an anthropologist and specialist in Afro-Cuban culture, who had been combing the island in her effort to compile and safeguard the songs and legends of the first Blacks to have come to the island. Alejo and Lilian Carpentier became the couple’s closest friends. Lam thus renewed his ties to the myths and rituals of his godmother Antonica Wilson. His sister Eloísa, very well versed in the cults of Santería, arranged for the group to attend initiation ceremonies and ceremonial dances to the sound of the beating drums. Cabrera, Carpentier and Guillén were convinced that the deported religion of African gods was one of the founding elements of Cuba’s cultural identity and at the origin of “magic realism” – a concept Carpentier created around 1940, which defines the cultural specificity of the Hispanic American world, with its roots plunged in the primitive, in folklore and myth – the marvelous that infuses its popular culture but also the marvelous adopted by Surrealism. Lam, by now fully sensitive to this, having fostered his own intimate relationship to the unconscious, re-established his ties to the practices of seers and magicians. And his figures are in large part inspired by the Orishas (divinities of nature from the Yoruba religion).

During this period of re-acquainting himself with the past, Lam also showed great interest for the new cultural developments. He often sought out the company of the Cuban poet and writer Virgilio Pinera, director of the review Poeta in 1942, the Cuban poet José Lezema Lima, founder of the review Nadie Parecía in 1941 and the soon to be review Orígenes (1944 – 1954) with José Rodríguez Feo. And his close friends, José Luis Gomez Wangüermet, Jorge Manach, Gaston Baquero, José Hernandez Meneses, Roberto Juan Diago Querol and Manuel Moreno Fraginals. He met Pierre Matisse for the first time who had come to Cuba to personally accompany Lam’s paintings to New York. And lastly, he had many friends among the foreign artists who were living in exile such as Robert Altmann.

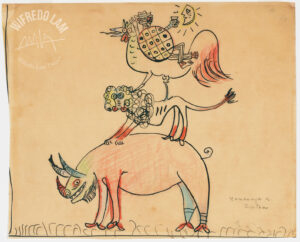

Toward the end of the year, after multiple trials with gouache and tempera, he began to compose La Jungla, the largest painting he had ever painted up to that point.

The Scandalous Jungle (1943 – 1945)

The completed painting of La Jungla captivated his friends. Pierre Mabille, who was enjoying a brief stay on the island, compared the importance of Lam’s work to Paolo Uccello’s discovery of perspective. He claimed it was a painting “in which life bursts forth, unfettered, dangerous, poised for all possible combinations, all transmutations and forms of possession.” No one, it seems, failed to see the impact it would have: “Dream of Eden,” according to Breton; “delirious vegetation,” according to Leiris; “revolutionary unrealism,” Fernando Ortiz; and later Max-Pol Fouchet wrote: “a barbaric poem, monumental, superb.” It’s a painting that describes “the convulsion of man and the earth”. In other words, Lam’s painting entered into resonance with the poetry of Césaire who called upon him to translate his Cahier d’un retour au pays natal into Spanish but Lam chose, instead, to entrust Lydia Cabrera with the task. Retorno al país natal, with a preface by Benjamin Péret and three drawings by Lam, was published in Havana in 1943.

Lam was pleased to see Mabille again who was in transit between Haiti, where the doctor, with his great knowledge of civilizations, had completed a series of conferences on Physical Anthropology and Biotypology, and the Yucatan, on a mission for the Institute of Ethnology. Mabille steered Lam to hermetic texts which, according to his new theory, had a link to the practices of voodoo (Paracelse; Martínez de Pasqually; Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin). Mabille and Loeb, both very interested in esotericism, also encouraged him to study the ties between religion and spiritism in Santería – disciplines related to the subconscious – but also to draw parallels between Western and Oriental philosophies, primitive civilizations and ancestral memory. On their way back, Mabille and Loeb invited Lam to accompany them to Santería and Abakuas ceremonies (the Abakua brotherhood was formed in the 19th century by the Africans of Nigeria with the aim of penetrating the meaning of the mysterious language of the tam-tams). They were accompanied by Carpentier who was writing a piece on musical instruments and Cabrera who was recording the songs of African slaves. These experiences and their guidance inspired Lam to use Nanigo symbols in his paintings.

This rich entourage filled Lam with inspiration as he continued to paint with fervor. Despite the fact that the New York exhibition of La Jungla in 1944 had created a scandal, he approached his subject with absolute freedom. The slight improvement in the political situation with the election of Ramon Grau San Martin as President combined with the death of his mother were undoubtedly factors in pushing Lam to work twice as hard. He married Helen Holzer and participated in the foundation of the committee Artistas Plasticos de Ayuda el Pueblo Español with the painters Ramos Blanco, Carlos Enríquez and René Portocarrero. He also became involved in the domain of music, becoming the Vice-President of Havana’s Chamber Orchestra (Philharmonic orchestra), which invited the conductor Erich Kleiber to Cuba. Kleiber later brought over the composer Igor Stravinsky. Meanwhile, the maverick Russian violinist Jascha Heifetz joined the orchestra, giving Lam the occasion to meet him.

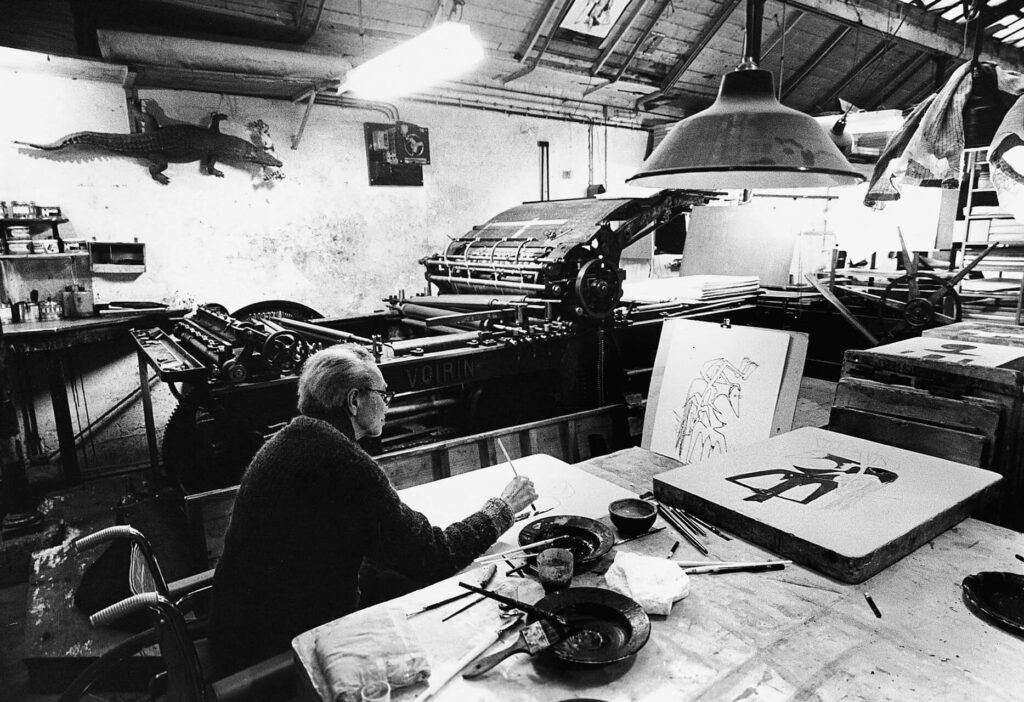

Just as the MoMA of New York bought La Jungla and hung it alongside a no less important work – Picasso’s Les Demoiselle d’Avignon – Sagua la Grande nominated Lam the title of “citizen of honor.” He chose to be present for the ceremony and used the occasion to show Helena around his birthplace of Sagua. His artistic activity expanded as he began experimenting with new techniques such as lithography. Lam made a lithograph for the cover of Loeb’s book Voyages à travers la peinture and to illustrate a poem by Yvan Goll – another European exile. Yvan Goll had stayed with Guillén before meeting up with Breton in New York. Lam also designed the covers of the reviews Orígenes and View (n°2) – a special edition dedicated to “Tropical Americana” and presented by Paul Bowles whom Lam met in Cuba. In May, Pierre Loeb had nothing but praise for his painter friend, writing in Tropiques: “Lam knows how to draw and paint, he’s read everything, he knows music inside out, he is the brother of our most sensitive modern poets; […] the magic we most desire, implore, search for, is within him.”

Anne Egger

(Translation by Unity Woodman)

(2) It is important to remember that African art was forbidden in its representation or reproduction during the slave period in the Antilles; likewise, it was forbidden to weave or sculpt. The slave, exiled without objects, had only the option of singing, dancing or recounting poems and fables

Journeys & Encounters

In 1945, Wifredo and Helena are invited to Haiti by Pierre Mabille, recently nominated Cultural Attaché for Free France. They attend the inauguration at Haiti’s French Institute, set in place in 1941 by Jean Price-Mars and the ethnologist Jacques Roumain to promote cultural diversity… Mabille has set up a library, comprised of books by such authors as Eluard, Desnos, Aragon, Vercors, Gorki, Neruda, Mayakovsky, Lenin, Prévert, Picasso, Métraux, Césaire…Wifredo and Helena arrive in late October with enough work to put together an exhibition. They are quickly joined by André Breton who has come for a cycle of conferences, accompanied by his new wife, Elisa Claro. After the ceremonies of December 7, a number of Haitian artists and writers organize a weekly reunion every Friday at the Savoy cafe, which they attend throughout their stay. In January 1946, the Lam exhibition begins in Port-au-Prince at the Centre d’art, which was opened two years prior by the American Dewitt Peters. The catalogue is prefaced by Breton with “La nuit en Haïti”. The exhibition is a triumph. Magloire Saint-Aude and Hector Hyppolite are captivated by his work. Above all, the event gives a boost to the community of local artists and naive painters whose work will be regularly shown at the center.

Voodoo and revolution

During the course of his stay, Lam comes to realize to what extent Cuba and Haiti share the same struggle. Since 1945, the hope that the fall of Fascism will lead to the fall of the dictators and authoritarian regimes throughout the Americas is a recurring thought. But it is in Haiti that he personally witnesses an insurrection. The climate of revolt that has been latent during Elie Lescot’s dictatorial regime – who was put in place by the United States in 1941 – explodes and in January the whole of Port-au-Prince takes to the streets. After the publication of Breton’s speech who openly expresses his opposition “to all forms of imperialism and white brigandage”. The review is forthwith confiscated by the authorities. Leaders of the movement are arrested and hunted down. The youth rally round Gérard Bloncourt, René Depestre, Jacques Stephen Alexis and protest. The army intervenes, topples the Lescot government but cut off the revolutionary youth. A campaign of defamation against Breton ensues who is treated as persona non grata, and especially against Mabille, treated as a spy working for Cuba and Mexico. In the meantime, Lam, Breton and Mabille attend eight voodoo ceremonies – a religion nevertheless outlawed by decree since 1935 – but all a Bembé (the celebration of the Loas religion, with drums, songs and dances in honor of Yemaya). The painter is fascinated. He finds the “wild” and “prodigious” possessions much more impressive than in Cuba; although Breton is less enthusiastic. They return to Cuba in early April to attend the inauguration of Lam’s first solo exhibition at the Lyceum in Havana where Mabille gives a conference. Despite his growing recognition, Lam is impatient to return to Europe now that it has been liberated. He will spend only two months in Havana. Far from his studio, he paints very little that year.

Cuba – New York (1946 – 1951)

Discovery of New York and a disappointing visit to Paris (1946)

At the end of June 1946, Wifredo stops over in New York, the biggest city he has ever seen, bathed in a crystalline, immaterial light, but very pictorial. Through Breton, he makes numerous encounters – with Marcel Duchamp and Jeanne Raynal who present him to Nicolas Calas, Roberto Matta, Isamu Nogochi, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, Sonia Sekula, David Hare, Gerome Kamrowski, Frederick Kiesler… A first contact marked by rich encounters and new friendships. He meets the composer John Cage, who is experimenting with contemporary music. On July 9, he sets off for Europe and reaches Paris after six years of absence. His euphoria is short lived, however. He is surprised by the atmosphere: on the one hand, an artistic world dominated by the diktat of “social realism”, and on the other, the quasi extinction/washed out of Surrealism, now considered a “counter-revolutionary idealism”. While it is a great pleasure to see his friends Picasso and Breton again, they are no longer on the same side. Picasso joined the ranks of the PCF (the French Communist Party) in 1944, while Breton’s voice is simple muzzled. In June, he participates in the exhibition at the Galerie Pierre, organized in aid of Antonin Artaud.

This is undoubtedly when he meets René Char. The poet’s encounter with Lam’s works fills him with wonder and is moved to meet the painter in person, whom he finds refined and subtle. They share their experiences of taking up arms – Lam on the side of the Spanish Republicans, Char with the French resistance – and agree that necessity calls for action to take precedence over art. Lam is overjoyed to reconnect with his friend Césaire who invites him to his Sunday reunions on Rue de l’Odéon where Lam is again in the company of Loeb, René Ménil and René Depestre. He meets Jean Cassou, chief curator at the Musée national d’Art moderne. Césaire has entered into politics but without abandoning his inspiration and his art. Wifredo presents Michel Leiris to the new mayor of Fort-de-France and deputy of Martinique, now a member of the Communist Party. Lam decides, nevertheless, to escape his Parisian milieu and, before visiting Italy and Germany in order to see what Europe has become on both sides of the “front,” he takes a short holiday in Cannes.

When he returns to Paris, Asger Jorn is there with a project for an international art review which he presents to Picasso and then to Pierre Loeb, and lastly to Breton, on his way back from the United States. But Breton is reticent when presented with the idea of fusing Surrealism and Abstract Art – as Jorn sees it, full of color and spontaneity – which characterizes the new Danish movement. But Breton presents Jorn to Lam who is captivated by his activism who will spend his whole life militating for the total freedom of art. He will later claim that Lam’s paintings marked him profoundly and they both share a great passion for music. Lam decides to return to his work in Cuba, taking with him a number of African sculptures from the Kota, Dan, Baolé, Bambera and Dogon tribes, as well as an Oceanic stone ax.

A radiant influence from Cuba (1947 – 1948)

The moment he gets back to work, Lam creates his series of Canaïma. The name evokes the south-eastern region of Venezuela where Carpentier is planning to travel for his newspaper El Nacional, but it is above all the title of a novel by Romulo Gallegos. The author, who wrote it during his exile in Spain (1935), exalts the Aboriginal, set within the jungle of his country and the forest of rubber trees. Gallegos will be elected President of Venezuela the following year, only to be deposed shortly afterward by the junta for his progressive ideas. For the Native Americans, Canaïma is a frenetic god, the principle and cause of all evil, a spirit at times haunts the savannah. Lam’s style gains in incisiveness as it evolves and an increasingly esoteric quality develops alongside the African and Oceanic influences. While Helena visits New York during the summer of 1947, Lam goes forward with his work. He has to participate in an exhibition on the other side of the ocean as the Surrealists are organizing the first major Parisian event since 1938. It is being conceived of as a sort of initiatory journey. Lam sends a lithography for the catalogue and, for the labyrinth, an alter dedicated to the “Chevelure de Falmer,” a line taken from Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror. He is also in the midst of preparing the hanging for his personal show at the Pierre Matisse gallery in New York. Despite the geographical distance, he continues to stay abreast of the cultural involvement of his friends in Paris. Césaire and Leiris have become part of the sponsoring committee for the new review Présence Africaine, founded by Alioune Diop. Its aim is to promote culture in Africa, or rather in the “Africas” – Black Africa, the Caribbean and French-speaking Africa, to breathe new life into a culture that has laid dormant for too long. Lam feels especially enthusiastic about this move which he feels is spawning independence movements throughout the post-colonial world. After a winter in Cuba, Wifredo spends the summer months of 1948 in New York where Helena has found work and decided to settle there. They receive invitations to spend time at Jeanne Raynal and Erwin Nuringer’s house and Lam undoubtedly takes an interest in Edgar Varèse’s comeback – a friend of Duchamp’s. He and Noguchi visit Gorky only a day before he commits suicide (July 21). They also visit Tanguy and make the acquaintances of the artist and architect Naum Gabo, of Frederik Keisler, the artist Maria Martins, introduced to them by Breton and Duchamp. It is Lam’s work – seen at the Pierre Matisse gallery – that ultimately stimulates Pollock to study Native American art.

When he returns to Cuba in November, Lam joins other artists in creating the Agrupacíon de Pintores y Escultores Cubanos (APEC). After his stimulating encounters with artists in the United States and being well-informed about artistic events in Europe, Lam tries to encourage artists, wherever he happens to be, to cooperate and create artist communities. He learns that Asger Jorn has created the CoBrA group, a group of Scandinavian artists who advocate greater freedom and spontaneity in art with an international and interdisciplinary focus. But it is also engaged art that has a social aim but without linking artistic research to political engagement – an approach that speaks to him for he has always succeeded in being politically engaged without adhering to a particular party and thus avoiding the trap of dictating what is and is not permitted in art. And hence his participation in the CoBrA movement remains a personal one. His production is not as abundant in 1949 as in previous years, but it remains impregnated with the Afro-Cuban oral culture. He works closely with Fernando Ortíz who is preparing the first illustrated monograph on the artist, Wifredo Lam, Y su obra vista a traves de signi ficados criticos. An important essay by Pierre Mabille on the genesis of Lam’s work appears in the Magazine of Art. While the local political situation shows little change, the painter no doubt follows closely the proclamation on October 1 of the Popular Republic of China after two years of civil war.

Ceramics and separation (1950)

Although they have been separated geographically for two years, Wifredo and Helena are on the verge of divorce. In Cuba, the year 1950 proves especially productive and Lam even tries his hand at making ceramics, at the studio in Santiago de Las Vegas, with Mariano Rodríguez, Amelia Pelaez and René Portocarrero. After the monograph by Ortíz is published, the Cuban government decides to offer Lam a grant to study the development of modern art in the United States, France and Italy, allowing him thus to travel abroad. Ever since the war ended, Lam is never in one place for very long. His travels are always exploratory and enriching, both on a cultural and friendship level. In the meantime, he is kept informed of his friends’ publications. Lam is especially marked by Césaire’s Discours sur le colonialisme and Leiris’s “Textes antillais”.

Anne Egger

(Translation by Unity Woodman)

1951 – 1962

A nomadic artistic life

February 1951 marked the inauguration of mural paintings by Lam, Amelia Pelaez, René Portocarrero, Carlos Enriquez, Jorge Rigol, Carmelo Gonzales Iglesias and Enrique More, commissioned by the Esso Standard Oil Company (in the Velado district) to adorn their offices. At the occasion, Lam met the journalist and militant anti-government activist Carlos Franqui who would soon preface the catalogue to his solo exhibition in Havana at the Sociedad de Nuestro Tempo gallery. In April, he won first prize at Havana’s Salon Nacional de pintura y escultura y Grabado for his painting Composition – a period marked by many awards. His divorce was finalized in May 1951, after which Lam returned to Europe for several months, leaving his house in the care of a Cuban friend, the surrealist-inspired writer and film-maker Edmundo Desnoes and his wife Maria Rosa. During the summer months, his surrealist friends commissioned a design for the frontispiece of their special edition of the new review L’Âge du Cinéma, consecrated to the movement and founded by Adonis Kyron and Robert Benayoun. Among the new artists to join the movement are Jean Schuster, Jean-Louis Bédouin, Michel Zimbacca, and Nora Mitrani. In Europe, his paintings took part in a number of CoBrA events: his participation in the 2nd large international exhibition of experimental art held at the Palais de Beaux-Arts in Liège, Belgium; and his drawings illustrated the September issue of the review CoBrA.

Dictatorship and another exile (1952)

When Lam returned to Havana, he was disturbed by the political developments on the island after the coup d’état instigated by Batista on March 10, 1952, giving rise, once again, to an army-backed dictatorship with all the repercussions that followed: repression, the end to the constitution, the proscription of political parties, the censorship of the press, the repression of political opponents and an inevitable rise in corruption. Lam decided to leave the “Banana Republic” behind him and to settle definitively in Paris. By late August, he settled in France and began preparing for a personal exhibition in London. He illustrated René Char’s aphorisms, collected in A la Santé du serpent. He closely followed the developments of the Phases movement and the creation of its eponymous review directed by Édouard Jaquer, Anne Ethuin and Jean-Louis Bédouin, which brought together such diverse artists as Pierre Alechinsky, Corneille, Götz and Max Walter Svanberg, the common denominator among these very different artists being their adoption of automatic writing in their art. Lam felt an affinity to this movement “without manifesto or fixed theory” or, expressed more poetically, “its modern conception of magic”. It adopted the motto, taken from Breton, “toute licence en art” (“any license in art”)!

In February 1953, Lam was invited to present several paintings to the gallery A l’étoile scellée, which opened the following year with André Breton as artistic director. A collective exhibition, dedicated to Surrealism, brought together works by Ernst, Tanguy, Man Ray, Toyen, Paalen and Lam. Soon after, he met up with Picasso in Mougins where Picasso took him to see a bullfight. Upon his return to Paris, he participated in a number of surrealist gatherings at the Parisian cafe on La Place Blanche. But Lam remained independent in both his artistic and political involvements, and would continue to maintain his independence throughout his artistic career. He joined Césaire every Sunday for afternoons of conversation with a group of friends, hosted by Césaire’s Martiniquan friends Dr Auguste Thésee and his wife Françoise. After a Creole meal, their animated discussions were the occasion for Lam to indulge in another of his passions: economics and politics.

Lam illustrated other publications: L’Arbre et l’Arme by Dotremont, alongside Alechinsky, Hérold and the Japanese-American sculptor Shinkichi Tajiri, and Le Rempart des brindilles by René Char. He designed the cover for Carte noire by François Valorbe, a collection of poems inspired by the great black jazz musicians. During the summer, Lam received news of the latest developments in Cuba and the armed response by Fidel Castro against Batista. What would come to be called the “Movement of July 26” was a failure: Castro and his comrades, Carlos Franqui among them, were charged with a 15-year prison sentence but would serve their sentence until 1955 before leaving in exile to Mexico where they met Ernesto Che Guevara. In September, Lam went to Italy to exhibit with 12 other artists at the Ecole de Paris, an event organized by Christian Zervos for which Lam won the gold medal of the Lissone Prize, awarded to foreigners, for his large canvas La Fiancée.

Times of many travels 1954 – 1961

In Paris, January 1954, Lam met the young writer and art critic Alain Jouffroy, excluded from the surrealist movement four years prior. He also met, in the Phases circle, the Rumanian poet Gherasim Luca, a friend of Brauner’s and Hérold’s, whose deep voice explored the French language with great originality, precision and anxiety. He had come to Paris in 1952 but remained stateless all his life. Another friendship developed with the Danish painter Wilhelm Freddie, also an exile, whose work created numerous scandals. Lam participated for the first time in the 10th Salon de Mai, to which he would remain faithful for many years to come. This yearly event, founded and organized by Gaston Diehl, Jacqueline Selz and Yvon Taillandier, was conceived in 1943 to give a venue and backing to modern art, and to put up resistance to the Nazi’s conception of degenerate art. It took place regularly, beginning in 1945.

Asger Jorn and the ceramicist Tulio Mazzotti sent Lam an invitation to participate in the International Meeting of Sculpture and Ceramics scheduled for August, 1954, in Albissola (Italy), a small seaside resort town on the Ligurian coast, known for its history of using terra cotta as early as the Renaissance. Hosted by Jorn and Enrico Baj, the creators of the International Movement for an Imaginary Bauhaus, the meeting brought together artists to work and experiment collectively. Appel, Corneille, Matta, Sergio Dangelo, Édouard Jaguer, among others, were present, but Lam arrived too late. By the time he got there, everyone had left. He nevertheless fell under the charm of the place and promised to return. The indefatigable traveler then took off once again, this time to Havana to discuss plans for an exhibition at the university. In Chicago he was presented to the collectors Edwin and Lindy Bergman, who had already acquired several of his paintings.

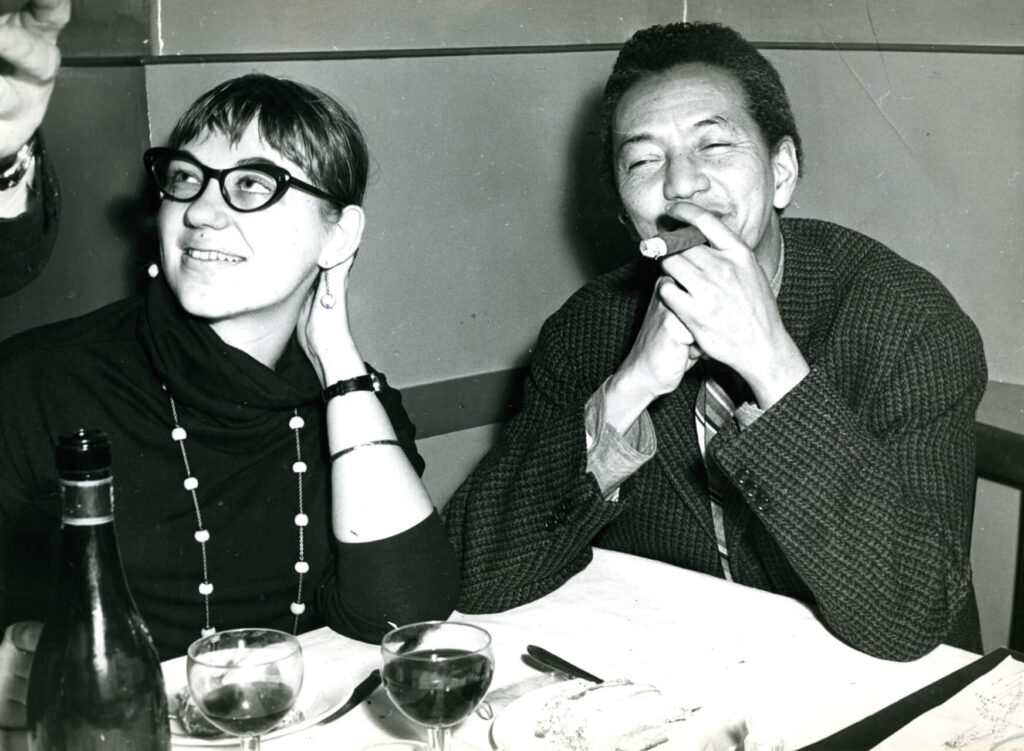

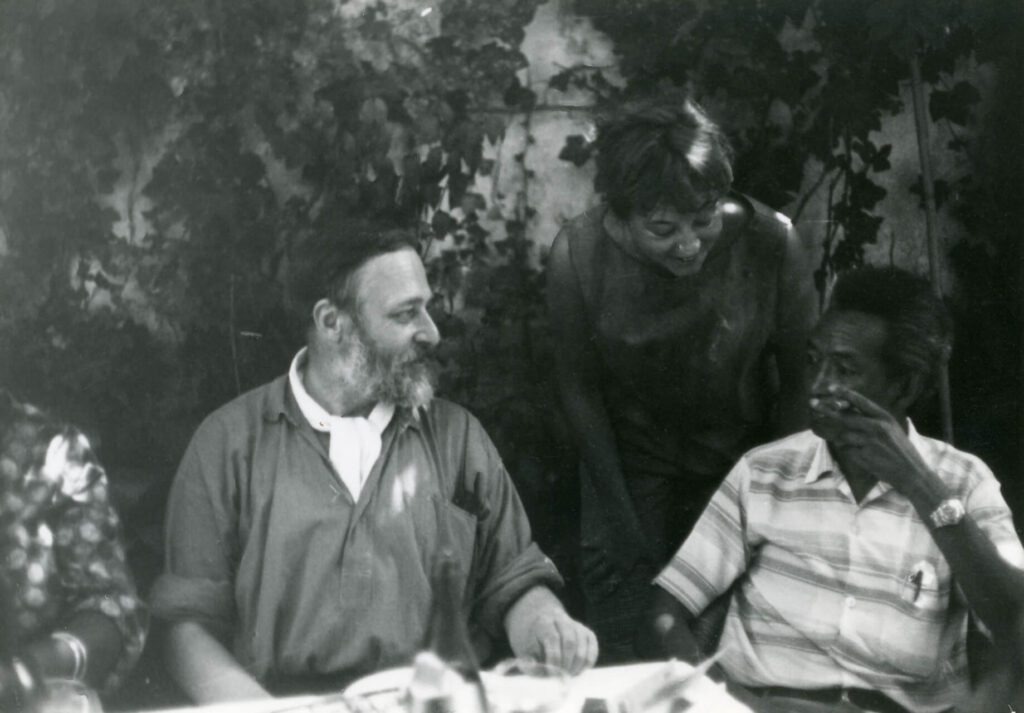

In Paris, he found housing at the Cité Universitaire, not far from his painting studio at the Villa Alésia. He stayed in close contact with the surrealists – illustrating the 4th issue of their review Médium – and in particular with Benjamin Péret, who described him as “the African sorcerer and Asian shaman – the two forces joined inside of him in an adventure to extend their powers.” Lam made a series of engravings for the collected poems of the Martiniquan poet Édouard Glissant in La Terre inquiète. In May 1955, he traveled to Caracas for the inauguration of his solo exhibition. He was also invited to the French Venezuelan Institute where its director, Diehl, gave a conference on his work entitled “Rimbaud and Lam.” Carpentier was also present as he was living there in exile. Lam was introduced to the architect Carlos Raul Villanueva, a meeting that led to a commission for a mural painting. Upon his return to Paris in late June, Lam met the young Swedish artist Lou Laurin at the Galerie du Dragon, during an exhibit of Latin-American artists. In September, he went to Sweden and participated in a collective exhibition Imaginisterna at the Colibri gallery which included other artists associated with the CoBrA movement. He took the time to visit the country, in particular Falun where Lou Laurin introduced him to her family.

Immediately following his trip to Sweden, he set off to Caracas, invited by his friend Villanueva, who had built the Ciudad universitaria. Lam had been commissioned to make a large fresco for the botanical gardens. Then in early 1956, in the company of Nicole Raul, he partook in an expedition to the Mato Grosso and had the occasion to fly over the great expanses of virgin forest and the Maroni, Orinoco and Amazon rivers. They spent several weeks in a camp set up by prospectors for gold and precious stones. He caught “the green illness” (a form of chlorosis) and had to return to Cuba for medical care. But he was soon back on his feet, just in time to prepare his exhibition at the university. Before honoring the commission of a large mosaic for the Centro Médico de Vedado, he learned from a letter that Césaire had broken with the Communist Party. In his Lettre à Maurice Thorez of October 24, Césaire expresses his disapprobation of the French Communist Party’s sectarianism and refusal to “undertake the path of de-Stalinization.” Lam, always opposed to dogmatism, approved of his friend’s reaction. As Lam prepared to leave Cuba, Castro, who had returned to the island undercover, was preparing his offensive with his guerrilla army in the Sierra Maestra Mountains. A solo exhibition opened in February 1957 at the Centro de Bellas Artes in Maracaibo, Venezuela’s second largest city, and soon after Lam attended the inauguration of his fresco at the botanical gardens in Caracas.

He returned to Europe just before the summer and spent the months of August through September in Italy with Lou Laurin. He met up with Brauner, Manzoni, Baj, Roberto Crippa and Fontana in Milan. During a short stay in Venice, the couple happened to meet Elisa Breton and Jean-Jacques Lebel, as well as Bona and André de Mondiargues, who shared Lam’s love of the country and his interest in the occult and magic. They finally returned to Albissola and to their friend Jorn. Jorn had developed intellectual ties with Guy Debord, creating the International Situationist movement. In November, the couple flew to Mexico, arriving in Mexico City the same day as the funeral of the muralist Diego Rivera. Lam met up with one of his oldest Spanish friends Anselmo Carretero, but also the ex-wife of Péret, Remedios Varo, who introduced the couple to Leonora Carrington and the collector Edward Silence. Lam’s friend Carlos Franqui, who had been imprisoned and tortured under the reign of Batista, introduced them to a number of pro-Castro refugees: the doctor Martha Frayde, the union activist Lazaro Pena and Castro’s university fellow Alfredo Guevara. Traveling through the country, Lam learned that his sister Eloisa had died. Toward the end of February, the couple left Mexico and returned to Cuba. Lam showed Lou Laurin around Havana, a dynamic and festive city, albeit corrupt. But the repressive climate spelled danger for the Castro guerillas, and a number of the painter’s friends were arrested. Mangiargues paid Lam a brief visit on his way through and the surrealist poet José Álvarez Baragaño. Baragaño, who was preparing a monograph on the painter, began interviewing him. Lam decided to leave Cuba, but before leaving he burned several of his large canvases – those he was not entirely satisfied with – while others he put in the care of his sister Augustina. He received news of the birth in Paris of Stéphane, his son with Nicole Raul. On April 9, the day of a general strike, the couple left for Miami, and then New York where a number of their friends awaited them: Jesse Fernández, Carlos Rigaudias, Eugenio Granell….

They landed once again in Europe and spent the month of August in Albissola, staying with their friends the Crippas, then Jorn. They then went to Rappallo where Enrico Baj was working with ceramics. Lam was enthusiastic about discovering this new milieu, brimming with friendship and artistic freedom. In Chicago, in October, he was elected as a member of the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. The city of art collectors, in Chicago there were the Neumanns and the Maremonts (20th century art), Muriel Newmann (American art after 1945), the Bergmans and the Shapiros (surrealist art). Immediately upon his return to Europe, Lam received news from Cuba that the “Movement of July 26” fighters had taken Santa Clara and were about to make a victorious entry into Santiago de Cuba and even Havana. Batista was forced to flee the country. The much hoped-for Cuban Revolution was in full swing. Fidel Castro finally took control on January 8, 1959, and began implementing the sort of reforms Lam and his compatriots had hoped for. But Lam chose not to return to the island like his friend Alejo Carpentier. In Paris, he frequently met with Marcel Zerbib, a publisher and the director of the Galerie Diderot. A chance meeting with Max Ernst and his wife Dorothea Tanning led to a collective project of illustrating the poems of Alain Bosquet in Paroles peintes. Matta and Hérold joined them. Lam participated in documenta II in Kassel. Initiated in 1955 by Arnold Bode, an artist whose work was forbidden during the Nazi regime, the original idea was to reconcile the German public with modern art and to gather together all the vibrant forces of artistic creation in the spirit of multiculturalism. It would take place every five years and last 100 days. In the year of 1959, more than 1800 works from 300 artists were selected.

It was not clear whether Lam met the poet and art critic Hubert Juin through Aimé Césaire or through René Char. Juin finished writing a book on Césaire in 1956. Lam would illustrate Juin’s current book project to be published in 1960 entitled Le Voyageur de l’arbre. And parallel to this, he made a number of lithographs to “comment,” in his own way, the poems of Alain Jouffroy. After the Salon de Mai and an exhibition in Venice from June to July, Lam and Lou Laurin spent another summer in Albissola, before returning to the United States. On November 21, 1960, they married in Manhattan and then made another visit to Chicago, invited this time by Lindy and Edwin Bergman. They were introduced to many other Chicago collectors: Jory and Joseph Shapiro, Claire Ziesler, Ruth and Leonard Horwich, as well as the art dealer Richard Feigen. Undoubtedly their stay was animated by lively discussions about art, but also about the situation in Cuba; although tempered somewhat in lieu of the stand taken by the U.S. government who break off diplomatic relations and set an embargo on Cuban products. Lam was hoping to see the revolutionary regime grow in international scope and, above all, to take the form of a worldwide anti-imperialist movement.

Painting and family life 1961 – 1962

After all these years of absence, the Lams were disheartened by the tension that pervaded everyday life in France, following in the wake of its involvement in the Algerian War. As a Cuban, Lam was again confronted with discrimination and decided, instead, to set up his life in Zurich and Albissola. His choice of Switzerland led to a greater appreciation of his graphic work. His engravings were chosen to illustrate Gherasim Luca’s poems in L’Extrême Occidentale, alongside works by Arp, Brauner, Hérold, Matta and Tanning. His prints also appeared in L’Oeuvre gravée and were solicited by the Galerie Mathieu. Lam closely followed the events unfolding in Cuba – the failed landing of the Bay of Pigs, backed by the United States and Cuba’s decision to receive aid from the Soviet Union. That same year, Chris Marker’s documentary Cuba si marked the first anniversary of the Cuban Revolution. The Lam couple rejoiced at the birth of their son Eskil, born in Copenhagen on May 24. The family spent the summer in Albissola and rented a house near their friend Jorn. Encouraged by Jorn, Lam tried his hand at ceramics.

Anne Egger

(Translation by Unity Woodman)

1962 – 1977

Paris Albisola

Anchorage and Internationalization of his art

In the year of 1962, Lam continued to travel extensively and to attend exhibitions, but he also created a number of engravings: for the new edition of Mabille’s Miroir du merveilleux, along with artists Hérold, Matta and Ernst; for Images, a portfolio produced and printed at Giorgio Upiglio’s print studio in Milan; for Carpentier’s last book, El Reino de este mundo. Despite the changes in Paris as the Algerian War came to an end on March 18, followed by Algeria’s declaration of independence in July, the family decided to remain in Zurich where Lou Laurin-Lam gave birth to their second son, Timour, on June 6. They returned to Alibssola for the summer, the place that held the most attraction for Lam. Their evenings were spent among friends at the restaurants Il Cantinone, Mario’s or at the Montparnass. Lam began looking for a house to buy and eventually found one in the Bruciati neighborhood. With some renovation to incorporate a painting studio, and work on the grounds, there would be a terraced garden with trees and an installation of his totem collection. This became Lam’s primary residence for the next twenty years. The children and the new property in no way diminished Lam’s preoccupation with world events: the missile crisis in Cuba, in particular, had the whole world on edge. After a tense moment, Moscow decided to stop its operations in exchange for a promise from the United States not to invade Cuba. Lam was equally troubled and shocked by the life imprisonment of Mandela, the leader of the ANC, whose condemnation was all the more disturbing considering he had taken up arms against Apartheid, in place since 1948.